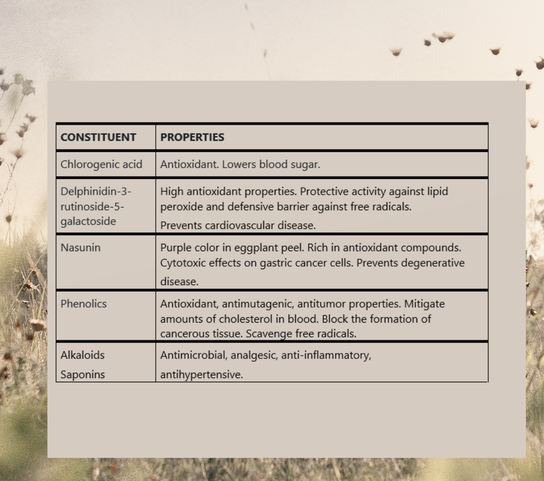

The flavonoid nasunin isolated from the peel of the eggplant fruit is a potent antioxidant and free radical scavenger and has been demonstrated to guard cell membranes from damage. EGGPLANT SEASON New Mexico's August heat brings the chiles and the eggplants. A new harvest every day. I pick the eggplants when they're soft and tender, no need to peel or salt, and then grill, roast, or stew. Eggplants stewed in soy sauce with chiles and garlic over noodles - my favorite comfort food from rainy days studying Chinese in Taiwan. HISTORY The eggplant (Solanum melongena) is a plant species in the nightshade family Solanaceae. Botanically a fruit, large eggplant (brinjal) are indigenous to India and small eggplant (茄子) are indigenous to China. The texture of eggplant brings an earthiness and heft to vegetable-based cuisines and vegetarian diets. Chefs recommend that eggplant not be stored hot or cold. It is highly perishable. Medieval Europeans were ambivalent toward eggplant, perhaps because of the bitter taste of earlier cultivated varieties. The literature warns about bitterness and pungency and the belief that eggplant creates a melancholic and angry mood. Salting and rinsing counteracted these properties, which are far less pronounced in current eggplant cultivars. Since the development of varieties without the bitter taste, the popularity of eggplants has increased. They are now celebrated worldwide for their health benefits and medicinal properties. MEDICINAL PROPERTIES Henry C. Lu notes in the Chinese System of Food Cures: Preventions and Remedies that eggplant nourishes the blood, supplements vegetarian diets, and contains vitamin P (flavonoids). Eggplant possesses anticancer and antioxidant effects and prevents hardening of the blood vessels. Historically, in Traditional Chinese Medicine, eggplant was used to treat abscesses as well as for intestinal bleeding and toothache. EGGPLANT STUDIES Pakistan Journal of Nutrition (2004). Rabbits fed a normal diet supplemented by eggplant had lower levels of lipids in the blood and increased levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (good cholesterol). There were strong hypolipidemic effects from Solanum melongena and Solanum gilo, as well as an improved HDL/LDL ratio, indicating eggplant's potential for treating ischemic heart disease and arteriosclerosis. Modern Medical Laboratory Journal (2018). The cytotoxic effects of eggplant peel extract on human gastric cancer cells and normal cells from a cell bank in Iran were investigated. Delphinidin 3-rutinoside-5-galactoside may have antioxidant properties and protective activity against lipid peroxide. A relationship between eggplant’s cytotoxic effects and its antioxidant activity has been demonstrated. Food Elixir Science (2014). An evaluation of the nutrient and phytochemical constituents of four eggplant cultivars found high concentrations of alkaloids, tannins, and saponins. Tannin compounds have antibacterial, antiviral, and antiparasitic effects, and alkaloids and saponins have antimicrobial properties. Polyphenols may promote the uptake of glucose in tissues and improve insulin sensitivity. Journal of Carcinogenesis & Mutagenesis (2013). Three steroidal alkaloids and two steroidal glycosides isolated from the peel of Solanum melongena L. exhibited moderate to potent activity against human cancer cell lines – activity was most pronounced against liver cancer cell lines. Subsequent in vivo testing against hepatocellular carcinoma in rats demonstrated reduced tumor marker levels. The compounds also restored levels of AST, ALT, and albumin. CHEMICAL CONSTITUENTS OF EGGPLANT Phytonutrients in eggplant include vitamin B1 (thiamine), vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), copper, manganese, potassium, magnesium, vitamin B3 (niacin), and vitamin B9 (folate). The flavonoid nasunin isolated from the peel of the eggplant fruit is a potent antioxidant and free radical scavenger; it has been demonstrated to guard cell membranes from damage. Flavonoids extracted from the fruits of Solanum melongena showed significant hypolipidemic potential in rats. The nightshade family is rich is alkaloids. Solanine is the bitter glycoalkaloid found in the vegetation and fruits of most Solanum species. Raw eggplant contains solanine and the fruit should be cooked before eating. Eggplant also has substantial levels of oxalates. If you have a history of oxalate-containing kidney stones, then you should eat eggplant in moderation.

Infants and children Avoid feeding raw eggplant to babies and toddlers. Eggplant contains compounds that may irritate the digestive system. Nitrates in eggplant convert to nitrites when cooked and may present a hazard to infants younger than four months. It is important to know the symptoms of nitrite poisoning. People with chronic inflammatory conditions might consider limiting consumption of eggplant until the cause of the inflammation is resolved. Please note: The medicinal properties of eggplant are described above for educational and historical purposes only. This information is not intended to replace the advice of a healthcare provider.

2 Comments

GERMANY In contrast to other countries (Turkey, Kuwait, Malaysia, and Australia), herbal medicine use is very high in Germany with rates soaring from 50% in 1970 to 70% in 2010. A 2019 online survey examining the role of herbal medicine in the German healthcare system reveals that herbal medicine use in the general German population is very high, and over 90% of regular herbal medicine users self-administer herbal remedies. Yet patients lack awareness of the potential side effects and potential interactions of herbal medicine. SURVEY DESIGN Based in part on a survey instrument from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey, the questionnaire used quota sampling to provide a representative picture of the German population. A total of 2906 people participated in the survey. Survey topics:

SURVEY FINDINGS

HERBS In the survey, herbal medicine was defined as all plant-derived products in natural form and as pills. Here are the properties and general indications of the herbs used most frequently in Germany. Peppermint (Mentha piperita) is used primarily to address digestive colic, cramps, and nausea. Of unknown origin, peppermint has been used by the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. Its potency is categorized as strong and it has slight emmenagogue effects. Chamomile (Chamomile recutita) is another traditional remedy used for digestive problems from gastritis to irritable bowel syndrome, to treat tension and irritability, and to promote sleep. Chamomile inhibits the growth of Helicobacter pylori, one of the causes of peptic ulcers. Cautions include allergic hypersensitivity (chamomile is considered a ragweed) and reduced absorption of non-heme iron. Potency is medium and German chamomile contains a strong anti-inflammatory constituent. Sage (Salvia officinalis) regulates menstruation and reduces sweating. It is indicated for hot flashes. Sage is also considered a digestive tonic. Native to Europe, sage possesses strong potency and is toxic in excess. Ginger (Zingiber officinalis) is native to Asia and has anti-emetic, appetite-stimulant, and analgesic properties (eases generalized body ache). Its antiseptic properties are beneficial for intestinal infections. Ginger is contraindicated in combination with NSAIDs and should not be administered to patients with ulcers or bleeding disorders. Potency is strong. Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) is native to Europe and northern Asia. It is a sedative, nerve tonic, and cardiac depressant. Valerian induces relaxation in the smooth muscles of the uterus, colon, and bronchial passages. Overdose causes fainting and vomiting. Valerian may cause diuresis, thus it is not suitable as a sleep aid. Excess use causes depression of the central nervous system. Potency is strong. Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) grows in temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. It is diuretic, tonic, and anti-allergenic, and it cleanses the blood. Stinging nettle is contraindicated in pregnancy and possesses medium to strong potency. St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), native to Britain and Europe, is used to treat depression and anxiety and as a liver tonic. Do not take St. John’s wort during pregnancy and do not combine with birth control pills, statins, antidiabetics, and anticoagulants. Life-threatening serotonin toxicity is possible when used in combination with other antidepressants. Potency is strong. Arnica (Arnica montana) is found in the mountains of Europe, the United States, and Canada. It is used externally for bruises, sprains, muscle aches, and pains. Arnica is poisonous and should not be taken internally. In conclusion, herbs were used most commonly to treat cold and flu, respiratory problems, and gastrointestinal disease. Perceived helpfulness of herbal medicine was greatest for insect bites, gastrointestinal issues, and respiratory problems. Herbal medicine was perceived as not very helpful for tinnitus and depression. SOURCES OF INFORMATION As expected, the internet was the most popular source of information but, paradoxically, participants expressed low trust in internet information. Pharmacists and physicians were viewed as the most trustworthy sources. Does this reflect the lack of a centralized, trusted source of public information on herbal medicines? POTENTIAL FOR HARM

The survey demonstrates that use of herbal medicine plays an essential role in the German healthcare system. Healthcare providers need to be aware of patient behavior, and the general public needs a trusted source of information.

Caution: Use of herbal preparations is not recommended without the advice of a healthcare provider. Substances in herbal preparations may interact with prescription drugs to eliminate therapeutic efficacy or induce toxicity. Citation: The importance of herbal medicine use in the German health-care system: prevalence, usage pattern, and influencing factors (Welz et al., BMC Health Services Research, 2019 19:952) COMPILATION OF QUALITY REVIEW OF DOCUMENTS (QRD) DECISIONS ON STYLISTIC MATTERS IN PRODUCT INFORMATION The European Medicines Agency (EMA) provides scientific and regulatory guidance to pharmaceutical companies whose medicinal products have been authorized in Europe. I encounter questions of usage and style and consistency daily in my Chinese to English medical translation practice, so I quite enjoyed poring over the minutiae of their decisions. Here’s what I found interesting from a cultural/linguistic perspective in the EMA's recent QRD decisions on stylistic matters in product information and drug labeling:

There’s more! Specifics on the use of Unicode symbols, when to spell out micrograms and when abbreviation is permitted, base units, unit dose pack sizes, and lots of details on maintaining consistency. Subscripts. Superscripts. Additional guidelines on the use of abbreviations. Read more about these decisions at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/compilation-quality-review-documents-qrd-stylistic-matters-product-information_en.pdf Paclitaxel (trade name Taxol) is derived from the bark of the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia) and is used to treat breast, lung, and ovarian cancer. In Agatha Christie's book A Pocket Full of Rye, the first victim is murdered when his marmalade is spiked with poisonous yew berries. What is popular lore on the poisonous or medicinal properties of the yew tree? Culpeper’s Complete Herbal & English Physician (1826) states “Many in this country have eaten yew berries and survived. The tree’s very powerful poisonous qualities rise by distillation.” He goes on to say that, despite these qualities, yew berries are “sometimes given usefully in obstructions of the liver and bilious complaints.” In The Complete Book of Herbs, Lesley Bremness notes that all parts of the English yew are poisonous, yet a homeopathic tincture made from the leaves and berries is used medicinally. In the homeopathic literature, the bark, branch tips, and needles of the yew are used to treat diphtheria, tapeworms, tonsillitis, liver conditions, and rheumatism. HISTORY OF PACLITAXEL In 1961, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) began screening thousands of plant compounds for their anticancer properties. Samples of Pacific yew were first collected in 1962 by researchers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) who were under contract to help the NCI in their search for natural products that might cure cancer. And compounds derived from the bark of the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia) showed promise. Extracts from this bark proved cytotoxic, although even after identification of the extract's most active component, it still took several years to isolate paclitaxel in its pure form. Testing was undertaken to identify the biological action of the new compound. It was not until 1977 that the NCI was able to confirm antitumor activity in a mouse melanoma model. Because of difficulties harvesting the drug and the complexity of synthesizing the compound, development toward the clinic was slow. The drug, however, showed effectiveness against mammary tumors and ovarian cancer, pushing researchers to find a means of isolating large quantities for clinical use. Clinical trials became possible when a method was derived to extract a precursor, 10-deacetyl-baccatin III, from the common yew. The precursor was then converted by chemical synthesis to paclitaxel. Today, a cell culture method is used to produce the drug. MECHANISM OF ACTION Paclitaxel is a novel agent that interferes with the normal function of microtubule growth; at high concentrations it induces mitotic arrest in the G2/M phase of cell growth, and at low concentrations it causes apoptosis in the G0 and G1/S phases. Paclitaxel promotes the assembly of microtubules from tubulin dimers and stabilizes microtubules by preventing depolymerization. This stability results in inhibition of the normal dynamic reorganization of the microtubule network that is essential for vital interphase and mitotic cellular functions. In addition, paclitaxel induces abnormal arrays or “bundles” of microtubules throughout the cell cycle. The drug binds to a cell's microtubule assembly and slows cell division and growth by stabilizing the microtubules, preventing shrinkage, and therefore blocking segregation of chromosomes. CHALLENGES It was difficult to formulate paclitaxel into a delivery system acceptable for human use. Initial activity was observed with bulk drug suspended in solution. Although paclitaxel was soluble in 75% polyethylene glycol, repeated testing using this formula produced inferior results. When the drug was formulated in an ethanol, Cremophor, and saline solution to a particular concentration, intraperitoneal activity was preserved at initial levels. Preclinical toxic effects were most evident in tissues with a high cell turnover, such as hematopoietic, lymphatic, gastrointestinal, and reproductive tissues. APPROVAL In 1992 the FDA approved paclitaxel (Taxol) for the treatment for ovarian cancer. Clinical trials to test treatment in other types of cancers and in combination with other therapies resulted in indications for breast cancer, lung cancer, and Kaposi's sarcoma. Frontiers in Pharmacology review article examines the safety of herbal medicinesEXPLOSIVE GROWTH OF HERBAL MEDICINES Viewed as a balanced and moderate approach to healing, herbal medicines have grown exponentially. This popularity is attributed to a preference for natural therapies and a greater interest in alternative medicines. Traditional medicinal practice involving herbs is an integral part of many communities, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 80% of the world’s population relies on herbal medicine as a primary source of healthcare. Strategic marketing by manufacturers of herbal medicines has expanded product visibility, and the continuous introduction of new herbal products into the market has led to public health issues and safety concerns. CHALLENGES All medicines must be safe and of suitable quality, yet a single herb plant may contain hundreds of natural constituents. Such complexity means that the control of raw herbal materials and finished herbal products is more involved than for conventional pharmaceuticals. A substantial proportion of the global drug market, herbal medicines require pharmacovigilance and safety monitoring. The WHO recommends national quality specifications and standards related to the manufacturing, import, and marketing of herbal materials; however, in most countries, herbal medicines arrive on the market without mandatory safety or toxicological evaluations and without evidence of quality and efficacy. The common misconception that natural products are nontoxic and devoid of adverse effects leads to improper use and unrestrained intake, along with the risk of severe poisoning and acute health problems. Herbal medicinal products have been implicated in cases of poisoning, with certain compounds capable of reacting with cellular macromolecules including DNA and inducing cellular toxicity and/or genotoxicity. SAFETY AND TOXICITY The safety of traditional and herbal medicines is paramount to national health authorities and the general public, yet:

Possible causes of adverse events resulting from the consumption of herbal medicines include mistaken use of the wrong plant species, misidentification of medicinal plants, adulteration of herbal products with undeclared medicines, mislabeling of herbal medicinal products, contamination with toxic or hazardous substances, overdose, and misuse of herbal medicines by healthcare providers or consumers – including concomitant administration with other medicines. Predictably, adverse event analysis with herbal medicines is more complex than with conventional pharmaceuticals. Evaluation of product safety is further complicated by geographical origin of the plant material, processing technique, route of administration, and compatibility with other medicines. PROPERTIES OF SPECIFIC HERBS Aristolochic acids and Aristolochia species. After findings of potential nephrotoxicity and carcinogenicity of aristolochic acids, studies confirmed their genotoxic activity. Aristolochic acid-related DNA adducts have been found in the renal tissues of patients; these mutagenic adducts are usually poorly repaired and capable of persisting for years in DNA. All plants in the genus Aristolochia contain aristolochic acids and are banned in Europe and the United States. Intake of slimming pills containing the Chinese herb Aristolochia fangchi has been linked to Aristolochic acid nephropathy and the development of subacute interstitial fibrosis of the kidneys and urothelial malignancies. The tubers and roots of the Aconitum species have been used medicinally for centuries in herbal preparations for stroke, heart failure, diabetes, rheumatic fever, painful joints, gastroenteritis, edema, bronchial asthma, and other disorders. Aconitum carmichaeli and Aconitum kusnezoffii are used traditionally for pain relief. The toxicity of these plants derives primarily from the presence of diester diterpene alkaloids. Severe cases of cardiotoxicity from consumption of aconitine-containing herbal preparations manifest as ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation and eventually death. Bradycardia and hypotension have also been observed. The toxicity of aconitine and related diterpene alkaloids can be denatured by special processing and in China only the processed (i.e., detoxified) tubers and roots of Aconitum can be administered orally. More than 70 techniques are applied to the processing of Aconitum roots in order to reduce levels of toxic alkaloids below a certain threshold; note that this principle is not accepted in Europe. Traditionally, Tussilago farfara or coltsfoot has been used for thousands of years to treat pulmonary complaints, acute and chronic coughs, bronchitis, laryngitis, and asthma. The polysaccharides are anti-inflammatory and immuno-stimulating, as well as demulcent, and the flavonoids have anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic actions. Tussilago farfara is generally regarded as nontoxic, although total alkaloids isolated from this plant have demonstrated hepatotoxicity. Recently, the effects of the pyrrolizidine alkaloids found in Tussilago farfara were reviewed and hepatic veno-occlusive disease and cirrhosis suggested as potential disease outcomes in humans. Restricted intake of pyrrolizidine-containing herbs is recommended. There are reports on the efficacy of Garlic (Allium sativum) for management of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. The main compound in the fresh plant is alliin, which on crushing undergoes enzymatic hydrolysis by alliinase to produce allicin. Due to the antiplatelet effects of garlic, care should be taken if given in combination with antiplatelet drugs and warfarin. Adverse effects associated with garlic extract include burning sensation in the gastrointestinal tract, nausea, diaphoresis, and lightheadedness. The active compounds of St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) include hypericin, hyperforin, and melatonin. The plant has clinically well-established effects for mild depressive symptoms, although allergic reactions, headache, dizziness, restlessness, fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, and photosensitivity have been reported, as well as hyperesthesia and a syndrome of dyspnea and hyperventilation with mydriasis, nausea, palpitations, and tremors. Interaction of St. John’s wort with antidepressants and anticoagulants has been demonstrated and use is not recommended in pregnancy because of the herb’s uterotonic activity. RECOMMENDATIONS It is vital to inform and protect the public by identifying risks associated with herbal medicines, incorporating herbal products into pharmacovigilance systems, linking safety monitoring to the regulatory status of herbal medicines, promoting safe use through adequate labeling and appropriate patient information, advancing knowledge of traditional, complementary, alternative, and herbal medicines within national drug regulatory authorities, and standardizing definitions and categorizations of herbal medicinal plants on an international level. Herbal medicines must be assessed for safety, toxicity, efficacy, and quality. Providers of medicines – physicians, nurses, and pharmacists – need training to understand how herbal medicines affect the health of their patients. Healthcare professionals and medical communicators (translators and writers) must inform the public. The right knowledge base is crucial. Citation: Ekor M (2014) The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 4:177. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177 Integrative Translations specializes in Chinese-to-English translation of conventional and complementary medicine.

Effectiveness of turmeric and tuina therapies |

�

AuthorKerilyn Sappington is the founder of Integrative Translations, which specializes in the Chinese to English translation of topics in conventional and complementary medicine. Archives

August 2022

Tags

All

|