Integrative Translations Blog

Kerilyn Sappington, Chinese to English Medical Translator

Antidiabetic Properties of Polysaccharides

Polysaccharide-rich foods have attracted growing interest for their therapeutic potential, particularly in the prevention and management of diabetes. Such foods may have hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and gut microbiota-regulating effects.

Winter Tonic Soup

Warm up your winter nights and get a boost of immunity with this recipe for Winter Tonic Soup!

Journey of the Chile

Chiles have been a part of human diets since about 7500 BC and they are one of the oldest cultivated crops in the Americas. In addition to their unique flavor, they also have many medicinal properties.

Neglected Tropical Diseases: Paragonimiasis and Clonorchiasis

Clonorchiasis and paragonimiasis are among the foodborne trematodiases targeted by the World Health Organization. This blog reports some of my recent translation work in the areas of global health, parasitology, and epidemiology and includes the life cycles of Clonorchis sinensis (Chinese liver fluke) and Paragonimus westermani (lung fluke).

Chinese Herbal Medicine in the Fight Against COVID-19

As a Chinese to English medical translator, I regularly translate case studies that combine modern pharmaceuticals with traditional Chinese medicinal herbs and acupuncture. Here, I update my 2020 blogs on the use of herbal formulas to treat COVID-19 disease.

In 2020, at the start of the pandemic, Chinese clinics encouraged the use of traditional Chinese medicine as early intervention in mild coronavirus illness. Today, in 2025, China’s official COVID-19 treatment guidelines still emphasize herbal remedies to relieve symptoms, differentiate syndromes, and support recovery.

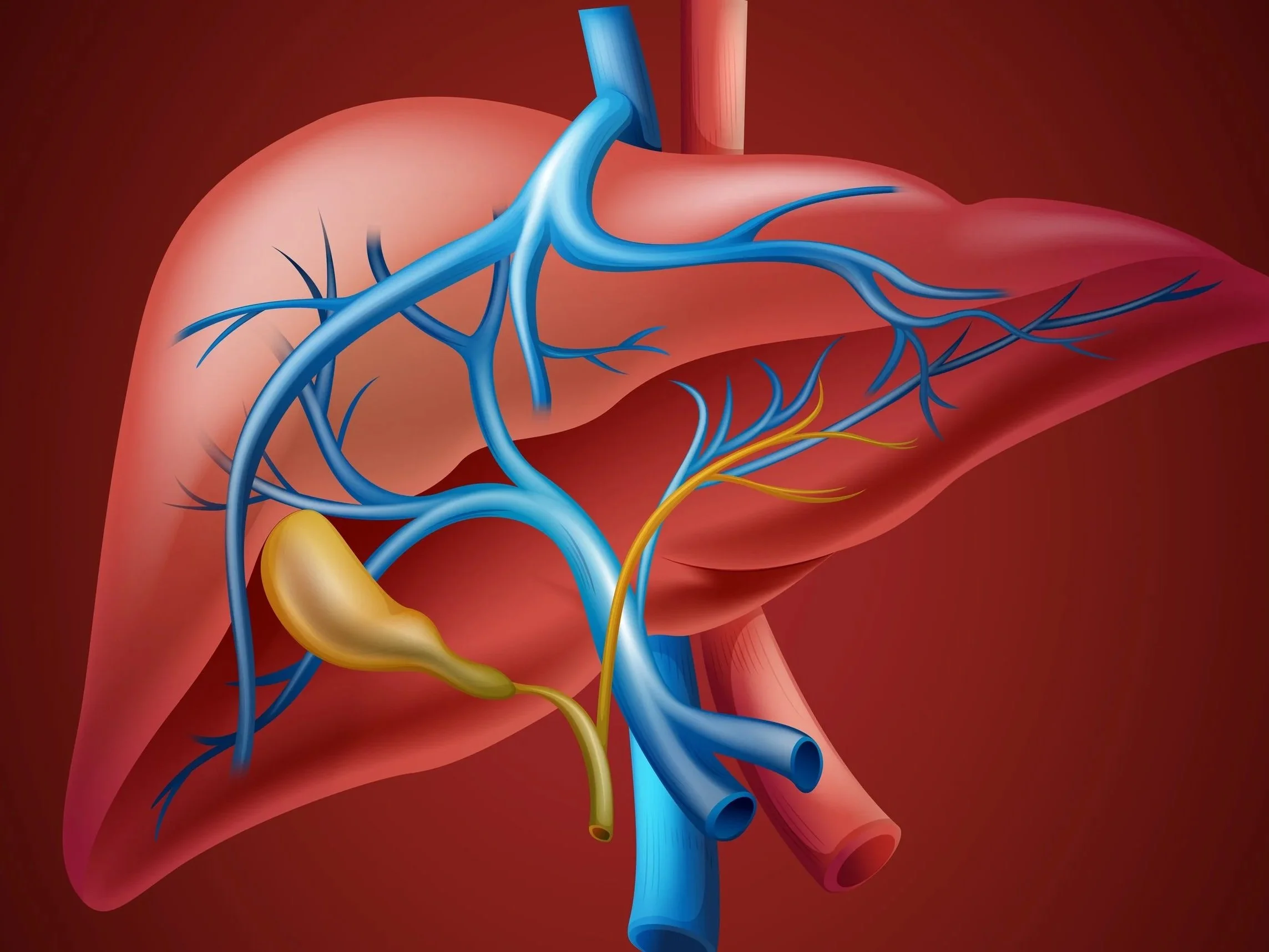

Herbs to Treat Drug-Induced Liver Injury

Chinese herbal remedies are used to alleviate liver disease, reduce severity of liver damage, and suppress the pathways and mechanisms of liver injury, among other hepatorestorative effects. Active ingredients include polyphenol compounds, flavonoid compounds, saponins, organic acids, terpenoid compounds, phenylpropanoids, polysaccharides, and alkaloids.

Basil, lemongrass, ginseng, and licorice root are just a few of the herbs with hepatoprotective and hepatorestorative effects.

Snake Venoms in Drug Discovery

Animal venoms for defense and predation are not a single toxin but are instead a complex mix of components (proteins, peptides, and enzymes) with specific biological and pharmacological activities. New drug development is one of the greatest challenges in the pharmaceutical industry today, and animal venoms have emerged as a source of therapeutic drugs. Over the past 75 years, potential therapeutic agents have been extracted and isolated from the toxins of plants, animals, and microorganisms, and in the past few decades several drugs have been isolated or derived from snake venom proteins.

Is This Document Korean, Chinese, or Japanese?

Chinese, Japanese, and Korean all use characters, sometimes they use the same characters. While modern Japanese is a mix of kanji (Chinese characters) and the katakana and hiragana syllabaries, most of the time Korean is written in the Hangul alphabet, although I have seen older Korean documents written with Chinese characters.

Integrative Medicine and the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis

Turmeric? Acupuncture? Tuina (therapeutic manual therapy)? What is the role of integrative medicine in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis? Here I take a brief look at two articles on the effectiveness of Curcuma longa (turmeric) and acupuncture for symptom relief and thrombosis prevention in knee osteoarthritis.

Yew Tree Bark: Or How Paclitaxel Became the Most Well-Known Naturally Sourced Cancer Drug

Paclitaxel (trade name Taxol) is derived from the bark of the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia) and is used to treat breast, lung, and ovarian cancer.

Behavioral Cardiology

In medical treatment today, heart health requires more than blood pressure control or the right pharmacologic therapy. Doctors advise lifestyle modifications in the form of diet and exercise yet may encounter resistance.