Antidiabetic Properties of Polysaccharides

The phytochemicals of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) may have benefits in the treatment of type 2 diabetes

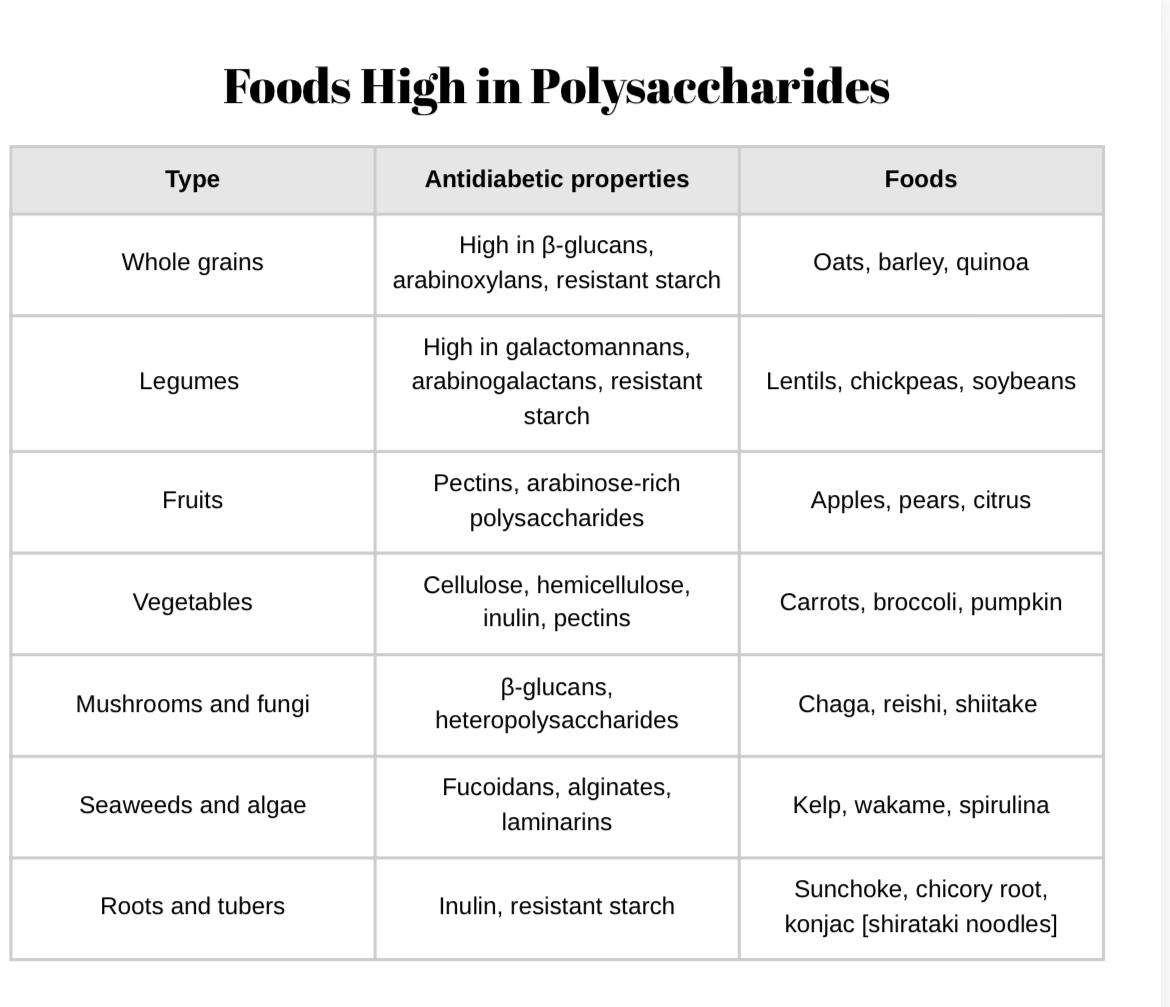

Polysaccharide-rich foods have attracted interest for their medicinal potential, particularly in the prevention and management of diabetes and other metabolic disorders. Naturally occurring polysaccharides from dietary sources—including cereals, legumes, mushrooms, seaweeds, and medicinal plants—exhibit a wide range of hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory activities and gut microbiota-regulating effects.

I recently translated a Chinese analysis of the mechanisms by which polysaccharides reduce glucose (regulating glucose metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and intestinal flora) and advances in the use of polysaccharides to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus, which precipitated a deeper dive into the medicinal properties of natural products as functional foods.

The chronic metabolic disease type 2 diabetes mellitus is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide and a major public health concern in China. According to data from the International Diabetes Federation and China’s Military Medical Research Journal, China has the highest number of adults living with diabetes in the world, between 148 and 233 million individuals and research suggests that more than half of diabetes cases are undiagnosed. The primary characteristics of diabetes include hyperglycemia, insulin resistance in peripheral tissues (adipose, liver, and muscle), and islet β-cell dysfunction.

POLYSACCHARIDES

The most diverse forms of organic molecules in nature, polysaccharides are long chains of carbohydrate molecules with immunomodulatory, radioprotective, antioxidant, regenerative, metabolic, signaling, antitumor, and anticoagulant effects, and their safety, low-toxicity, and hypoglycemic activity underscore their importance in the research and development of antidiabetic drugs. Polysaccharide activity varies depending on the interaction with the corresponding cell membrane receptor. A polysaccharide binds to a specific structural region, activates the receptor, and then initiates the intracellular signaling pathway. Activity is also strongly determined by molecular and structural features. Chemical structure determines stability, solubility, and interaction with proteins or receptors; monosaccharide composition, types, and ratios affect recognition by enzymes and receptors. Glycosidic bonds (both linkage position and anomeric configuration) control resistance to enzymatic degradation and the ability to bind biological targets. In addition, polysaccharides can adopt different conformations in solution (random coil, single helix, triple helix), which affect biological recognition. Polysaccharides may help with cholesterol excretion. The branched structure of polysaccharides and their large numbers of active hydroxyl and carboxyl groups are stabilizing complexing agents that combine with trace elements and synergistically carry out hypoglycemic activity.

POLYSACCHARIDES AND INTESTINAL FLORA

As macromolecular carbohydrates, many polysaccharides, particularly those classified as dietary fiber, are not easily digested in the stomach and small intestine. Indigestible carbohydrates from food intake constitute a major carbon source for intestinal microbiota. Because they are not easily hydrolyzed by digestive enzymes, these polysaccharides reach the colon largely intact and form a major component of dietary fiber, slowing glucose absorption, moderating postprandial blood glucose spikes, and improving satiety. Certain gut microbes ferment polysaccharides into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), supporting gut health and a healthy microbiome and associated with a reduced risk of inflammatory disease. Through gut fermentation and the production of SCFAs, polysaccharides aid in regulating intercellular signaling pathways and promoting a beneficial intestinal microbiota.

GUT MICROBIOTA AND DIABETES

The complex intestinal flora ecosystem is closely associated with type 2 diabetes. Disorders range from increased Proteobacteria, reduced Actinobacteria, changes in the Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio, increased conditional pathogenic bacteria, and reduced butyrate-producing bacteria. Alterations in gut microbiota diversity are associated with the development of type 2 diabetes, partly through disrupted energy metabolism, chronic low-grade inflammation, increased intestinal permeability, and immune-mediated insulin resistance. Modulation of gut microbiota by dietary polysaccharides has emerged as a promising strategy for improving the metabolic dysfunction associated with type 2 diabetes.

Because polysaccharides are administered as dietary supplements, functional foods, and experimental therapeutics to help manage diabetes and its complications, it is crucial to understand their digestion, absorption, and activation in the gastrointestinal tract.

Mucilaginous polysaccharides soothe dry or irritated tissues and support normal elimination processes. Many nondigestible polysaccharides function as prebiotics, selectively promoting the growth of beneficial gut microbiota while inhibiting potentially harmful microorganisms. As soluble dietary fiber, polysaccharides can slow glucose absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, bind bile acids, and promote their excretion, thereby influencing lipid metabolism. These properties contribute to reduced cholesterol absorption and improved bowel regularity, including relief from constipation.

NATURAL PRODUCTS

Polysaccharides from plants and fungi can modulate the composition and function of gut microbiota and ameliorate metabolic disturbances associated with type 2 diabetes. Certain mushroom and plant polysaccharides with antioxidant or immunomodulatory activities, such as beta-glucans, may contribute to immune regulation and the reduction of oxidative stress. Polysaccharides isolated from natural products (mushrooms, okra, kelp, pumpkin, and yam) hold promise for the treatment of diabetes and are being investigated as potential adjunctive strategies for metabolic disease management.

MEDICINAL FUNGI

Ganoderma lucidum (灵芝 or reishi) is a medicinal mushroom used extensively in Chinese medicine for over 2000 years. Polysaccharides from Ganoderma lucidum lower concentrations of inflammatory factors, improve low-grade chronic inflammation, reduce the outflow of plasma triglycerides and non-esterified fatty acids, and inhibit ectopic lipid accumulation in peripheral tissues and lipid generation regulated by hepatic insulin. Ganoderma lucidum significantly reduces fasting blood glucose and insulin levels and helps to maintain a balanced gut microbiota with high microbial diversity, functional stability, and resilience.

Inonotus obliquus (桦褐孔菌 or chaga) is a medicinal fungus that contains the monosaccharides mannose, ribose, rhamnose, glucose, galactose, xylose, arabinose and fucose. Chaga has antioxidant, glucose-lowering, and lipid-lowering properties.

Poria cocos (茯苓 or fu ling) is a traditional Chinese medicinal herb administered for its diuretic and renoprotective effects. Key components include triterpenes, pachyman, and pachymaran. Poria cocos has been shown to increase butyrate-producing Lachnospiraceae and beneficial Clostridium clusters, elevate intestinal butyrate levels, improve intestinal mucosal integrity, and activate the intestinal PPAR-γ pathway.

Phellinus linteus 桑黄 (sang huang) increases the number of SCFA-producing bacteria, increases SCFA levels, maintains intestinal barrier function, reduces lipopolysaccharide levels in blood, alleviates systemic inflammation, and reverses insulin resistance.

One of the most studied “medicinal mushrooms,” shiitake contain beta-glucans, polysaccharides, sterols, and antioxidants.

SEAWEEDS AND ALGAE

Laminaria japonica (海带) is cultivated as food and raw material for the production of iodine, mannitol, and alginate. It contains fucoxanthin, a xanthophyll that shows potential for treating type 2 diabetes.

ROOTS AND TUBERS

Amorphophallus konjac (魔芋块茎) is a root vegetable native to Yunnan China with high levels of glucomannan and fiber. Starch extracted from the cooked corms is edible and used to make noodles, jellies, fruit candies, vegan seafood, and as a thickening or stabilizing agent in food and drink. The cooked corms have various traditional medicinal uses. Potential health benefits include improved digestion and blood glucose management. Shirataki or “miracle” noodles are celebrated for their low-calorie, high-fiber properties.

Ophiopogon japonicus (麦冬块根) modulates the gut microbiota in mice fed a high-fat diet, increasing beneficial taxa and reducing potentially pro-inflammatory Proteobacteria, while partially restoring SCFA production.

Table of the antidiabetic properties of certain foods

LIMITATIONS OF POLYSACCHARIDES

The limitations of polysaccharides as therapeutic agents include complex and heterogeneous molecular structures, pleiotropic biological activities, and interactions with multiple molecular targets, all of which complicate elucidation of mechanism and research and development. Further investigation is required to identify the active components of polysaccharides and clarify their therapeutic targets and molecular mechanisms. Comprehensive understanding of polysaccharide pharmacodynamics is essential, as well as standardized quality control, reliable pharmacokinetic evaluation, detailed structural characterization, and systematic studies of hypoglycemic mechanisms, bioavailability, and in vivo metabolism and distribution – especially following chemical modification.

Despite these challenges, bioactive polysaccharides derived from natural products represent promising candidates for the development of novel hypoglycemic agents, owing to their favorable safety profiles, broad biological activity, abundant natural sources, and relatively low production costs.

Pumpkin fiber contains high levels of cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin.